‘It’s coming on Christmas, they’re cutting down trees.’ Do you know that Joni Mitchell song? ‘I wish I had a river I could skate away on?’ It’s such a sad song, and not really about Christmas at all, but I was thinking about it tonight as I was decorating my Christmas tree and unwrapping funky ornaments made of Popsicle sticks, and missing my mother so much I almost couldn’t breathe…

You’ve Got Mail (Norah Ephron, 1998)

It has always amused me when colleagues who have small children suddenly develop a research interest in children’s television or Disney films and start to write research papers on the viewing habits of under 5s. Now I am hoist by my own petard. Every film I look to at the moment seems to have grief as its controlling principle. I’ve always thought that about some films of course – Nora Ephron’s famous rom coms are explicitly about loss and the despair that comes with it. In Sleepless in Seattle, Sam (Tom Hanks) is recently widowed and still in the first throws of bereavement. In You’ve Got Mail, the loss of her bookshop brings back to Kathleen (Meg Ryan) all the pain and grief associated with the death of her mother. As she says ‘It was like she’d died all over again’. I love those films. They’re feel-good films. But in a sense they take as their central emotion something that doesn’t ‘feel good’ really, at all.

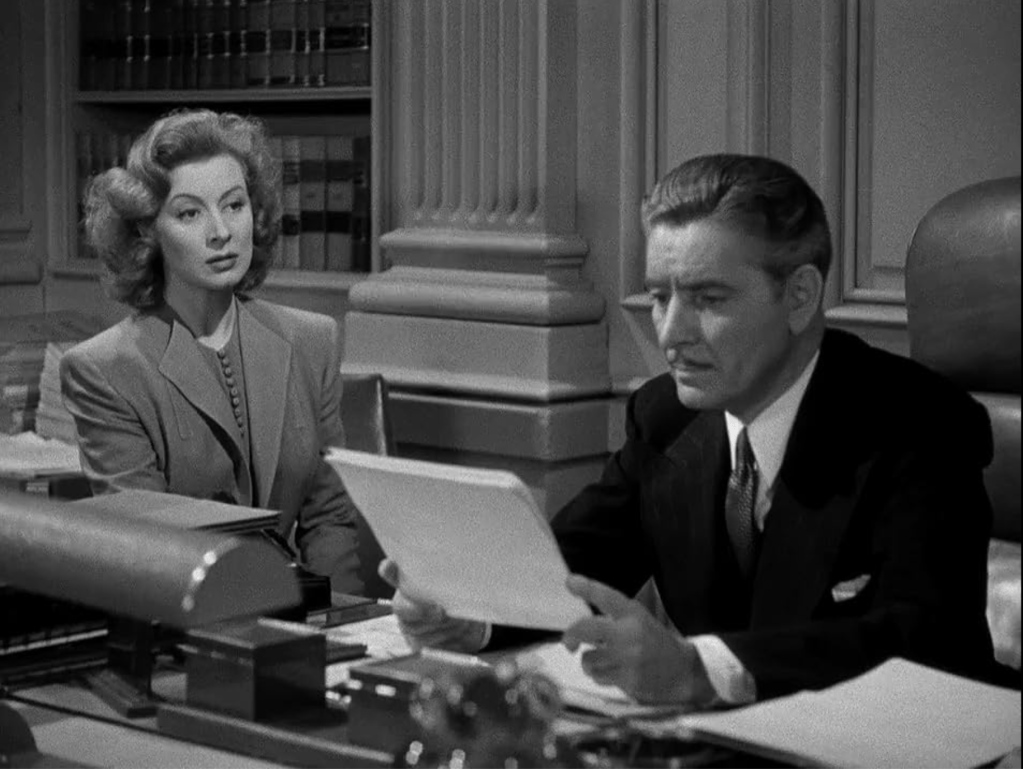

At the moment I’m supposed to be writing about Random Harvest (Mervyn LeRoy 1943). The film is about a lot of things I suppose – shell shock, memory loss, romance – but I can’t get away from the feeling that centrally, what it’s really about, is grief. Is it really about grief, or is it that just at the moment I am only able to read it in that way? People often say of films, ‘well of course it’s really about… blah’ and I always distrust that kind of statement – films are about all sorts of things to all sorts of people. They mean different things to those same people at different times. But even so I do have a sense that Random Harvest is infused with grief. The film has a complicated architecture which I can’t describe here, but if you know it you’ll remember the scene where Charles Rainier (Ronald Coleman) unwittingly touches the raw nerve of his secretary’s grief when she reminds him that she was once married:

“Oh yes to be sure, it slipped my memory. You had a child I believe?”

“Yes. A little boy. He died.”

This exchange has a devastating effect in the film, not just because it is the first time we learn of the death of her son, but also because throughout the scene she has been hiding her emotions from him, and here again she reveals her grief as though through a mask. Both characters are highly mannered – in the sense that they have good and elegant manners and they use them on each other. And good manners precisely have the function of masking emotion – that is their purpose. The scene is shot in such a way that, while Ranier is in profile, turned slightly away from us and towards her, she sits with her face directly facing the camera. She never looks at it, of course, because that is taboo in Hollywood film-making practice of this period. But her face is presented directly to the audience, who are invited to scrutinise it for the emotions we know she is experiencing, but is also masking from him.

In my recent experience, grief feels like this turn to the camera. It’s directed to a third party somehow – an audience out there in the darkness that you can’t see, and who can’t intervene. One rarely bursts into tears in the middle of work – that would be bad manners. Despite my fears I never cried in front of the students (although I did tell them what had happened and they were all very nice to me about it). When one is alone, too, one is kind of primed for emotion and tears are rarely sudden and unexpected.

Instead it is when one is both alone and yet at the same time somehow in public that the wave of recognition and despair comes over you unexpectedly in the familiar and repeated way – the sudden and uncontrollable tears of grief. Sometimes it happens from an unexpected reminder, sometimes just from a sudden place your thoughts arrive at when wool gathering. I have burst into tears in Lakeland Plastics in front of the display of soda streams, reminded suddenly of how much Mark had spent on the new soda stream he’d optimistically ordered online from his hospital bed, but which arrived after he’d died. And in Tesco I’ve burst into tears in front of the new Christmas season’s display of Lebkuchen – the German Christmas treat that he loved. But mostly I’ve burst into tears on busses and trains, because my undirected thoughts had returned, as they do again and again, to his last weeks – the final visit, the closing words, the brutality and finality of the end. On these occasions, it seems, I am always surrounded by uninterested strangers. Turning to the window to hide my tears and save embarrassment. Not ashamed. But alone in company.

This alone-in-company feeling is definitely something very central to my experience of grieving. Shortly after Mark died a friend told me that she’d found grief to be a lonely experience. Something that despite the support of loving friends and family, you must go through alone. And during my teaching this year, I’ve recognised this feeling being expressed in a number of the films I’ve taught, through the unusual device of the look towards the camera.

I’ve written before about the way in which this look is used in The Two Columbines (Harold Shaw, 1914). A mother, revealing a shabby Christmas tree to her daughter, throws us a glance of despair while her child is occupied in delight at the tree. The look makes us complicit in her sorrow at their poverty and shame, an emotion carefully hidden from the daughter. In Falling Leaves (Alice Guy, 1912) the look to the camera is similarly deployed. Little Trixie has noticed that her older sister is unwell. She overhears the doctor telling her parents that by the time the last leaf in the garden falls, her sister will have died. The scene is rather beautifully arranged – it is a single shot and all the meaning is achieved through gesture and blocking. Trixie is in the room, but in the background, while the doctor is talking to her mother. She’s not exactly un-noticed, but it’s clear that her mum hasn’t really registered her presence or she’d have bundled her out of the room. Trixie knows this and is paying close attention – she moves further into the background as the interview continues, the doctor moving to the window and making a gesture indicating the falling leaves. When her father (superhot Darwin Kerr in a very unflattering grey wig) enters, Trixie moves more purposefully out of sight – she knows adult stuff is going on, and that she risks being banished from hearing if she’s noticed. The doctor repeats the gesture towards the window. Only after the adults have left does Trixie emerge from her hiding place. She moves towards the window and looks out to the garden, then she looks to us. She climbs up to get a better view, and again looking at us, makes the gesture the doctor had made. Only we, the invisible viewers, are there to acknowledge what she knows – that her sister is dying.

Falling Leaves is relatively well known. When Mark went into hospital for the final time last year it was the week I was teaching it. I remember noticing the Christmas Cactus on the windowsill of the bathroom was just coming into bud, and wondering whether by the time the flowers had dropped he’d still be around. He wasn’t. I almost threw the plant in the bin when it started budding this year. I didn’t though, and the flowers are now dropping. I guess I’m stuck with it now – every year; a reminder. As though I needed one.

Less well known is Noël de guerre (1914) produced by Films Georges Lordier and written by Félicien Champsaur. I know nothing about these figures, and the film is collected on a disc of 1914-1918 films distributed by Pathe – 1914-1918: 4 Courts Métrages Muets. It stars Léon Bernard as a middle aged postman grieving for his dead son. When he and his wife are first introduced, their grief is depicted in clear and predictable ways. Returning from the cemetery in their mourning clothes, she sobs into her handkerchief while he lights the lamp. She gazes at a photograph of the child, and kisses it, and then crosses to the empty cot and breaks down again. He gazes at the photograph too, but seeing her at the cot, crosses too to comfort her. They embrace. Looking at photographs, contemplating empty furniture and spaces in the house made strange by absence – these are familiar enough gestures of loss. They are subtly rendered here, although in the acting style of the period. A very brief later scene depicting a ‘Soirée de tristesse’ shows them both facing the camera – she lit by the fire to the left of the screen, and he by the lamp above the dining table. She stares forwards bleakly while he smokes his pipe and looks alarmed at the extent of her grief. Again, he crosses the frame to comfort her.

The next day in the sorting office, he enters as his colleagues are laughing at the naïve letter of a child whose father is away at the war, addressed to ‘little Jesus’ and asking for some new toys. The scene is carefully blocked to rhyme the earlier one with his wife. He stands on the right of the frame, contemplating the emotions of those on the left – in this case, the unthinking mirth of his colleagues. As the letter is dropped into the dead letter basket, he raises his eyes and looks directly into the camera. The letter has a meaning for him that has escaped his workmates. His look makes us complicit in his emotion. He fishes the letter out, reads it again, looks at us once more and pockets it. When he reads it out to his wife, they agree to give the child the toys of their own lost son.

The final scene of the film, where he delivers the toys to the little boy on Christmas day, pretending they have been sent in response to the letter, is a masterpiece of acting and direction. He greets the child, showing him the letter and offering the parcel. With the boy’s mother’s consent, he embraces the little boy and helps him open the parcel, partaking fully in the boy’s excitement at the toys. But then he moves off again to the right, as the mother crosses and kneels with her son. A closer shot shows them both partaking in the joyous contemplation of the model trains and the clown doll contained in the parcel. When we cut back to the full shot, the postman is more thoroughly isolated on the right of the frame – separated from the mother and child by a completely different emotion which has overwhelmed him. He raises his hand to the side of his face, literally hiding his despair from the happy family, as the shot fades and the film ends.